4. The hills teem with the skeletal silence of dead life forms

Immaginavi tu forse che il mondo fosse fatto per causa vostra? Ora sappi che nelle fatture, negli ordini e nelle operazioni mie, trattone pochissime, sempre ebbi ed ho l’intenzione a tutt’altro che alla felicità degli uomini o all’infelicità.

G. Leopardi, Dialogo della Natura ed un islandese

The first characteristic that Morton identifies as structural in hyperobjects is viscosity. The sticker on the rear-view mirrors of American cars – OBJECTS IN MIRROR ARE CLOSER THAN THEY APPEAR – clearly describes our way of relating to hyperobjects: at the basis of the relationship between the individual and the hyperobject there is a pervasive and unrecognised closeness, which, according to the author, makes these entities somewhat threatening. Living in a state of deep interrelation with hyperobjects leads us to a widespread feeling of estrangement from the implant of reality, to feeling «at home in feeling not at home»1. It is the viscosity of the hyperobjects that brings to the bosom a trace of unreality, a weird irruption from, and of, an unknown dimension.

In La nausée, Sartre introduces the concept of viscous by describing the excess of materiality with which acts and feelings are charged. The viscous is a sticky liquid that catches the subject when he tries to take possession of an object, it is the sensation perceived by a hand immersed in honey: the sense of fading generated by the sugary death of the for-itself. As Amedeo Vigorelli reports:

Apparently docile, the viscous ends up possessing me […]. The solid object, which I release from my hand, gives me the impression of a real grip and of a victory of the for-itself over the in-itself. The viscous object […] gives me the opposite impression: of a compromise of the for-itself. 2

Unlike the relation between solid object and subject in which a strict separation between the two entities is maintained, the viscosity of the object has consequently a compromise of the subject starting from the object. For this reason, «every subject is formed at the expense of some viscous» 3, in the ontological interconnection in which we are already involved. The hyperobject, despite being immersed in our world, is not knowable in its entirety because, in turn, it envelops us, presenting itself as part of the known world.

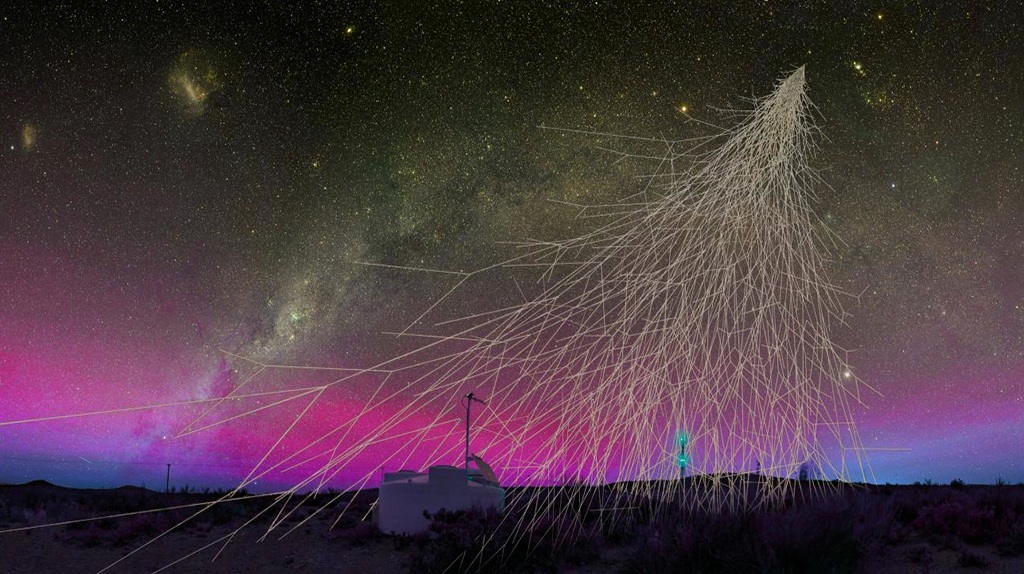

Non-locality, the second property identified by Morton, contributes to the non-visualizability of the hyperobject in its entirety: although we can perceive and systematise global warming, it is not here. To explain how this can happen Morton uses quantum theory: although, as a non-materialistic theory of physical substances, it is used by antirealism to necessarily correlate reality and perception, it is instead the only theory able to establish that things exist independently of their being perceived. Non-locality is a term that derives from Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen’s quantum paradox: if two particles, originally linked to each other, are separated and placed at opposite edges of the universe – according to the formalism of quantum mechanics – each measurement made on the first particle will instantly give us the value of the second, regardless of the distance between the two. The nature of the paradox is that where the measurement of the second particle at a distance is possible, then the existence of signals travelling at a higher speed than that of light would be implied. According to Morton, it follows that

Unless you want to believe that the speed of light can be violated— a notion that gives physicists the jitters—you might have to accept that reality just is nonlocal. Nonlocality deals a crushing blow to the idea of discrete tiny things floating around in an infinite void, since there is strictly no “around” in which these things float: one is unable to locate them in a specific region of spacetime. 4

Although hyperobjects are the physical substratum capable of justifying non-locality, their action at a distance is not non-local in the same way as that of a quantum. The principle of non-locality admits the possibility that at a deeper level of reality there is nothing that can be defined as local, because locality, if so understood, would be nothing more than an abstraction: since the pouring rain on the face is part of the experience of global warming and since global warming, as a hyperobject, is constituted as non-local, our experience of time is constituted as a false experience. Non-locality does not renounce the specificity of things by letting them sink into the general, but on the contrary it means submission of the general to the particular: «When I look for the hyperobject, I don’t find it (…) just is droplets, flows, rivers». 5

This is how non-locality leads us to temporality. What links the hyper-object to Fisher’s weird is the strange familiarity with which the individual can face the world: we know time and light, but time has been corrupted and light is only the refraction of a radiation. We must think of our relationship with hyperobjects as that between a body and the water in which it is immersed: it is something other than water, and yet, at the same time and with just contact, it produces ripples, receiving in return a progressive withering of the skin. The two entities, separated, are united by the reciprocal causality from which it is not possible to abstract: «Space can no longer be construed as an absolute container, but rather should be thought of as a spacetime manifold that is radically in the universe, of it rather than ontologically outside it» 6. According to the temperature tables of the Godard Institute for Space Studies, 75% of the effects of global warming will still be present for five hundred years: the ocean currents, in thirty thousand years, will absorb most of the carbon compounds, but 25% will still be present in the atmosphere. Finally, in 100,000 years it will still be possible to detect 7% of the effects of global warming. At the time when humans will be nothing more than fossils – the time when skyscrapers will be one of the submerged geological strata – the effects of the hyperobject in which we are immersed today will still be present. This, in addition to showing how hyper-objects move beyond the relationship with human subjectivity, brings out the persistence of «These gigantic timescales are truly humiliating in the sense that they force us to realize how close to Earth we are». 7

If Christian philosophy began the reflections on infinite spaces and times, it is with Einstein that space and time began to be conceived as emerging properties of objects. Einstein’s space-time, according to Morton, is a hyper-object: it is the way in which matter deforms space from within, transforming the universe into something like a torrent studded with countless whirlwinds of energy. Space-time, in this way, presents itself not as an empty container in which objects are placed, but as a force field generated by the objects themselves; since objects do not float in an infinite empty space, each entity persists in a time that belongs to it. Considering the insuperability of the speed of light «every event takes place within a light cone that specifies what counts as past and future (…). But outside the light cone, differentiating between now and then be- comes meaningless, as does differentiating between here and there (…). Time as such is itself an aesthetic phenomenon». 8 According to Morton, from these premises, it follows the necessary existence of a weird time, placed beyond its measurement, an elsewhere which is not in any place, but which, at the same time, is configured as a real entity in the universe. Hyperobjects make it possible for the futural aspect of objects to emerge. The non-local manifestation of hyperobjects is given by their transdimensional nature: if we see only a few fragments this happens because our perceptual point is placed within a single dimension, ours. A hypothetical multidimensional being, therefore, would be able to visualise global warming as a static object. If we, as human subjects, see only a few fragments of it – the points where it intersects our world – the intersection, in the case of global warming, manifests itself as an apparently singular climatic agent. What is related, is the static nature of anthropomorphized nature and its potential fluidity:

Thinking things as Nature is thinking them as a more or less static, or metastable, continuity bounded by time and space. The classic image of Nature is the Romantic or picturesque painting of a landscape. (…)We can animate this picture and produce an oozing, flowing, lava- lampy version of the same thing. 9

The resulting fluidity is not a point of arrival: such a movement transforms the static image into a moving image, although remaining within the paradigm of time as a container. When Deleuze, in his treatises on cinema, describes the relationship between image and time, he postulates the fading of the former into the latter: an image-movement, pure movement drawn out of bodies. Process philosophies such as Deleuze’s can in this case help us visualize multidimensional entities: separating objects and relations ontologically prevents the passage to a new ecological era; hyperobjects are real objects that are composed within relations. When times, irradiated by different entities, intersect, the pattern that comes to form is called phasing. Phasing is thus delineated as an oscillation on a given fullness from which hyperobjects seem to come and go because of our limited access to them.

The phases of the moon, the celestial events, are a continuous and persistent entity whose trace is impressed in our space, giving itself as singular: we experience isolated segments at the expense of an entirety that is never perceived as such, but is requalified in self-sufficient fragments. Our own measurements take place in the form of periphrases: since the number is such as it is computable – a number is a number if it implies a numerable object – mathematics does not lie at the basis of phenomena, but derives from them. The hyperobject, which cannot be grasped through the exclusive use of the senses, needs mathematical entities in order to be visualised: mathematics thus takes the form of an instrument capable of bringing the unknown back to the familiar, making the unthinkable intuitable. Proceeding in this direction, the weird of the hyperobject turns out to be the weird of the Earth itself:

A claustrophobic universe unveils itself to us, crammed with things: radiation, solar flares, interstellar dust, lamp- posts, and lice. Expressionism abolishes the play between background and foreground. 10

In order to be translated into readable information, the hyperobject crosses countless perceptive, mathematical and linguistic sieves. The phasing generated results to be an «an indexical sign of an object that is massively distributed in a phase space that is higher dimensional» 11 compared to the instruments used to measure it. The irremediable ontological caesura that materializes between the thing and the way it appears to other things makes all relations move on one, the same, side of the crack, leaving the outside lying on the opposite one. Human intersubjectivity, according to Morton, is but a subset of a more extended interobjectivity, a local and anthropocentric portion – an anthropocentrically connoted interobjectivity – of the interobjective dimension: the abyss that opens up to create the crack is not in space-time as a container, but between objects, and in its sharing with them. Starting from cable systems in which light bulbs, cables, computers, solar panels interface in such a way that energy flows as uniformly as possible, Morton extends the scope of the phenomenon to what defines the web. The web is described by Morton as made up of infinite connections and infinitesimal differences, capable of forming itself both in the relationship between the wires and in the space between the wires; each entity, in the web, does not exist on its own and is never entirely and only “itself”. Even the “inside” and the “outside” need in this way a rethinking: the web, in its paradoxicality, makes the boundaries between subjects and objects, between objects and objects, blurred: if a form of life must have an edge to filter what suits it and what does not suit it, then these boundaries are not perfectly defined; “An oyster makes a pearl by secreting fluids around a piece of grit it has accidentally absorbed. Surgeons can transplant organs» 12, and this also happens on a large scale. 13

The ecological thinking to which Morton refers does not make any kind of distance possible: the “here” and the “there” are the result of the metaphysical illusion composed of the clear separation between inside and outside, while all beings are connected to each other in a differentiated way, within an open system without centre or edge. The transmission of information within the network is not perfect, but leaves gaps: it is precisely these spaces that, by difference, make the entities become graspable. The hyperobject shows us how our experience of the world is not direct, but filtered by countless entities in a shared space: with Heidegger we could say that “we do not hear the wind in itself, just the door slamming”. According to Morton, interobjectivity nullifies the difference between cause and sign because «for every system of meaning, there must be some opac- ity for which the system cannot account»14, and that the system itself must include or exclude in order to persevere in its own state. The entities themselves define as present a boundary drawn arbitrarily around the thing, but that present does not exist, if what we experience is but a series of causal-aesthetic force fields emanating from a multiplicity of objects. Since time is not similar to a series of hour-points but to a wavy ocean, the crack between appearance and essence corresponds to an a-spatial one between present and future. Between these two elements the present is nowhere to be found because objects, by their nature, can never be present. Al-Rāzī, an Iranian philosopher and doctor who lived in the 9th century, claimed that some substances, such as gold, glass and gems, although very slowly, are subject to degradation. If we extend the alrazian intuition to every entity, the result is that the same celestial sphere is destined to disappear over thousands of years. We can hypothesize, with Al Rāzī, that the time of degradation of a ruby compared to a heap of grass can be proportional to that between a celestial body and the ruby itself. The same hyperobjects are linked to a life that, one day, will end. This finitude, however disproportionate compared to ours, forces us to live with a «strange future, a future “without us”» 15, which is present in the pervasiveness of an unthinkable exterior.

References

M. Colquhoun, Egress: on mourning, melancholy and Mark Fisher, Repeater, London, 2020.

G. Deleuze & F. Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1980), tr. B. Massumi, Minnesota UP, 1987.

G. Deleuze, Cinema I: The Movement Image (1983), tr. J-P. Manganaro, Continuum, 2005.

M. Fisher, The Weird and the Eerie. (2017), Repeater, 2017.

S. Freud, Das Unheimliche (1919), tr. it. S. Daniele, hansebooks, 2017.

A. Greenspan, Capitalism’s Trascendental Time Machine, PhD Thesis at University of Warwick, 2000.

G. Harman, Critical Animal with a Fun Little Post, in «Object-Oriented Philosophy», 17 Ottobre, 2011.

T. Morton, The Ecological Thought, Harvard University Press, Harvard, 2010.

T. Morton, Hyperobjects, Minnesota UP, 2013.

J. P. Sartre, L’être et le néant, Editions Gallimard, 2017.

A. Vigorelli, Il disgusto del tempo, La noia come tonalità affettiva, Mimesis Edizioni, Milano, 2009.

- T. Morton, Hyperobjects, cit,. p. 28

- A. Vigorelli, Il disgusto del tempo. La noia come tonalità affettiva, Mimesis Edizioni, Milano, 2009, p. 82 (my translation)

- T. Morton, Hyperobjects, cit,. p. 31

- Ivi, p. 42

- Ivi, p. 54

- Ivi, p. 56

- Ivi, p. 60

- Ivi, p. 67

- Ivi, p. 72

- Ivi, p. 76

- Ibid.

- T. Morton, The Ecological Thought, cit., p. 69

- «You only have to think of a coral reef to realize how life has influenced Earth; in fact, you only have to breathe, as oxygen is a by-product of the first Archæan beings (from 2.5 billion years ago back to an undefined limit after the origin of Earth 4.5 billion years ago). The hills are teeming with the skeletal silence of dead life forms», Ibidem.

- T. Morton, Hyperobjects, cit,. p. 89

- Ivi, p. 94